The Ugly

I began this meditation with a consideration of where we are with regard to the Bahamas’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. There are some good things. The elements that the government can control it is working on. Our response has been both proactive and nimble—it’s informed by data, it’s very open to suggestions from the public. It’s designed by experts. It changes with the changing times.

But there are too many elements beyond our control that will have an impact both on how we fare and how we survive long-term.

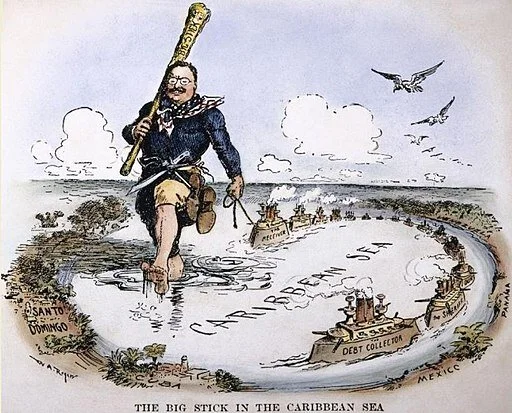

The first is the very structure of the government itself. It’s over-centralized and fundamentally colonial. Too much power is concentrated in too few places, and not enough authority is shared. Nassau is the be-all and end-all of all decisions, but the majority of Nassauvians have visited Miami more often than they have set foot on any other island. Without true devolution of power to local authorities, we’re stuck. We’re stuck with big-country problems and small-island imaginations.

The second is our leaders’ lack of experience in crafting policies for the public good. The—I’ll use Gilbert Morris’ word—cronyism that governs our politics guarantees that it is all too often not merit or ability but perceived loyalty that results in nomination for political seats. Talent gets selected almost by accident. Too many MPs and ministers are given power with very little understanding of the responsibility that comes with it, and worse, with no accountability other than having to run for election every five years. It’s a toxic system, and precarious.

And the third is the uneven development of The Bahamas, which stems from the first two, and which is unconscionable almost fifty years after independence. We live in a nation where we have nineteen major airports but only three hospitals, two of them in the same city. There is no public air ambulance system that serves our island populations. Airlift is slow and expensive. The price one pays for living outside New Providence or Grand Bahama can literally be death.

I ended the last meditation on the fundamental inequality that is our reality: the laissez-faire economy we have adopted, which leads government to take a back seat and allow the “market” to reign with little guidance or control. This model has left decision-makers so unused to making their decisions according to the common good, so practised in ignoring the actual lived reality of Bahamians, that now, faced with a crisis that comes up from the community and spreads through the community, we are at risk of making grave errors.

We saw that this past week with the introduction of the total lockdowns. So little notice of the shift from the regular curfew to the total lockdown was given that people panicked, flooded stores, and ignored social distancing entirely. A move that was intended to slow the spread of the virus almost certainly ensured that in two weeks’ time, we must see a spike in the number of infections.

Lockdowns are necessary

Now don’t get me wrong here. Locking down our society is really the only option we have to tackle the community spread of the coronavirus. What is most remarkable about our experience of COVID-19 is that, unlike so many of our Caribbean neighbours, the vast majority of the cases identified are the result of community spread. This makes lockdown inevitable.

I realize that there are those who will argue that the only long-term solution is the development of “herd immunity”; but they argue this without grasping what that process actually means in human terms. It’s one thing for epidemiologists who work in labs to propound the theory; and, quite likely, in theoretical terms, they’re correct.

But in human terms? The concept is difficult for any democratic government to contemplate.

Because here’s what it means in human terms.

It means letting the virus run its course. Letting it infect the population at will. Returning to the world in which “nature, red in tooth and claw” does the dirty work for us.

It means letting the virus carry off those who are too weak to withstand it; the survivors will probably be immune. And their immunity will be the seed of the new society.

In The Bahamas, there’re some problems with that:

Our population is fundamentally unhealthy.

We have a very high rate of obesity, and obese people appear less able to survive the virus

We have high levels of diabetes and hypertension, and people who have diabetes and hypertension are less able to survive the virus

We have elevated levels of respiratory disease in New Providence, and people who have respiratory diseases are less able to survive the virus.

Our population is poorly served by hospitals. I mentioned this already, but here’s what it means in concrete terms:

While we have a solid health care system as far as basic needs go, the clinics and the nurses we have scattered throughout our archipelago are in no way prepared to treat COVID-19. To treat it, we need hospitals with Intensive Care Units. Of these we have only three.

Of those three, only two are functioning well enough to really begin to tackle the coronavirus challenge. No one has said it out loud, but the Rand was seriously compromised by Hurricane Dorian and has not yet regained full functionality. More than that, we also know that it was challenged even before Dorian to meet the needs of the Grand Bahamian population.

Finally, the two hospitals in New Providence are located within one block of one another, and are located far away from many of the residents of New Providence. Our island is not large, but it is congested. The strain that would be placed on those two hospitals if we were to go the route of allowing herd immunity to develop would, quite simply, break our health system.

3. The people who are most at risk of contracting the virus are healthcare workers.

This means that if we let it run its course, we risk losing the doctors and nurses who keep us healthy in ordinary times. The only way around this is to shut down the hospitals as well, and let nature do its do.

What democratically elected leader—what kind of leader, in any situation—could seriously contemplate this? The only people with such luxury are lab scientists. People charged with looking after the business of other people don’t really have this option.

So forget the herd immunity scenario. It’s an idea that works well in labs, but the democratic politicians who decide to go that route would be signing the death warrant for thousands of the people they represent. It is not feasible.

So locking down the society—completely locking down—is the best option we’ve got.

Socializing the Science

But it’s not perfect.

Last Monday, when I listened to the PM announce this weekend’s lockdown in the House of Assembly, my feelings were mixed. The first feeling was: yes, this is the right move. But the second feeling was: but no, it’s the wrong way to do it.

What was clear to me, listening to the announcement of the expansion of the emergency order, is that while the PM and the Minister of Health are being advised by the medical profession—by scientists—they are not receiving parallel advice from social scientists—people whose expertise lies in how people behave: in ordinary times, in times of crisis.

Doctors deal with disease—things catalogued and categorized by the behaviour of microbes, with treatments and protocols that are designed to change the course of the disease. Most doctors trained in traditional western settings are taught to analyze, diagnose, and treat diseases, but not to engage with people. Doctors’ jobs are focussed on the thing they can most control—the diseases which are subject to swabbing, isolating, studying, culturing, examining under microscopes, finding treatments or cures, testing, controlling, eradicating.

People, alas, are the wild card in this equation.

The problem with treating people is that spark of independence, that unpredictability, that resides in each individual. And while in the normal course of events this can be dealt with one-on-one—with stern warnings about your life, with chastisement and changes of treatments and other doctors’ tricks—it doesn’t work when dealing with groups of people. Crowds—what social scientists call aggregates, what Shakespeare called “the mob”—behave differently from individuals, but just as unexpectedly. So you can devise a protocol for limiting community spread of a disease all you want. What you cannot do is guarantee that the community will follow it—or how they do so if they do.

This is what social scientists study. This is what we do. Social scientists, and particularly those of us who deal with human culture and behaviour—sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, criminologists, political scientists, social workers and counsellors—know that groups of people don’t follow the same logic that obtains in the lab. So when working on solutions, it’s not as simple as just telling the group what to do.

It’s how you tell them that matters.

The great thing? We’re learning. This government is learning, and—and this is staggering, giving the general impermeability of politicians—our leaders are asking for help. Our Prime Minister and our Minister of Health have put out a public call to citizens for ideas. Something fundamental is shifting. With all the bad, something unique is happening here.

Weighing the Risks

Lockdown is important, and lockdown is necessary. But it isn’t always safe. It may be the best thing for society, but for many of us it is a terrible thing for individuals. Our homes are not all equal, and our home lives are not all secure. We are not all able to regard lockdown as something that will save our lives; for some of us, it may well end them.

I’m one of the fortunate. Our house isn’t very large and our garden isn’t either, but it is secure, it is walled, have an office from which to work, I have vegetables in my garden. My job is secure and I am getting paid this month. My husband is supportive. We are both well, so far. Being locked down for me is an annoyance, nothing more. And sometimes it’s actually a gift; I get to sit in my garden and read and, sometimes, write.

But I find myself thinking more often than I find comfortable about those who are not so well situated. Whose homes are uncomfortable, even unsafe. Whose families are dysfunctional and violent. Those people who have to leave every day simply to get food and water; whose lives are outside most of the time because they still occupy yards; who are still living in overcrowded and tense conditions because they were left homeless from the hurricane. Most of these people will get no paycheck now. And I wonder how the lockdown is affecting them, and what is being planned at the levels of leadership for them.

Our leaders have a hard job.

Impossible really; we don’t know what’s coming and we have to take the best decisions we can under the circumstances. We will not get it all right. And we have a responsibility to be critical when we mess up—because our country is too unequal and too many of our governments have allowed and even encouraged that inequality to develop and grow.

We have to guard against tyranny, we have to guard against normalizing our lack of freedom. We are too close, even 200 years later, to the fundamental unfreedoms our society was built on, and we have to resist it at every turn.

I remain concerned that many of the rules of the lockdown risk criminalizing poverty as we have criminalized misfortune. So as we learn, and as we adapt, and as we change, let us be mindful of the good, the bad, and the ugly.